Inside the KOL Round: A Wealth Experiment Driven by Hype and Influence

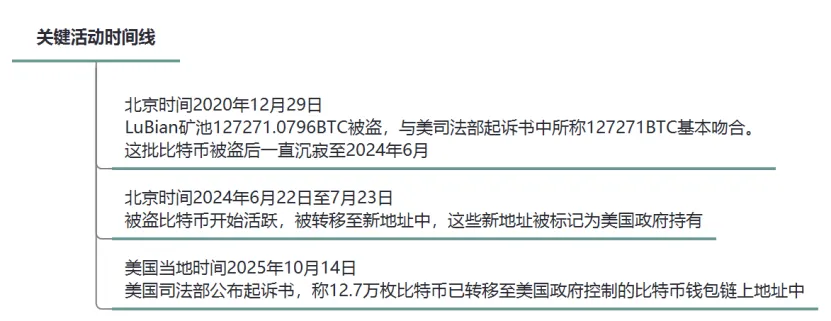

On December 29, 2020, the LuBian mining pool experienced a major cyberattack, resulting in the theft of 127,272.06953176 BTC (valued at roughly $3.5 billion at the time and now worth $15 billion). The assets belonged to Chen Zhi, chairman of Cambodia’s Prince Group. Following the breach, both Chen Zhi and Prince Group published multiple blockchain messages in early 2021 and July 2022, appealing to the hacker for the return of the stolen bitcoin and offering a ransom, but received no reply. Notably, these bitcoins remained dormant in attacker-controlled wallets for four years, with virtually no movement—behavior uncharacteristic of most hackers seeking quick profits. This suggests a precisely executed operation, more akin to a “nation-state hacking organization.” The stolen bitcoins were not moved again until June 2024, when they were transferred to new wallet addresses, where they remain untouched.

On October 14, 2025, the U.S. Department of Justice announced criminal charges against Chen Zhi and the seizure of 127,000 bitcoins from him and Prince Group. Evidence strongly indicates these bitcoins, seized by the U.S. government, are the same assets taken in the 2020 LuBian mining pool hack. This implies the U.S. government may have used technical hacking methods as early as 2020 to acquire Chen Zhi’s 127,000 BTC—a textbook “black-on-black” operation orchestrated by a state-level hacking group. This report analyzes the technical aspects of the event, traces the stolen bitcoin, reconstructs the complete attack timeline, evaluates Bitcoin’s security mechanisms, and aims to provide valuable security insights for the cryptocurrency industry and its users.

1. Background of the Incident

Founded in early 2020, the LuBian mining pool quickly rose as a major Bitcoin mining pool operating primarily out of China and Iran. In December 2020, LuBian suffered a large-scale hack, losing over 90% of its bitcoin holdings. The total stolen—127,272.06953176 BTC—closely matches the 127,271 BTC cited in the U.S. DOJ indictment.

LuBian’s operational model centralized mining reward storage and distribution. LuBian did not hold bitcoins in regulated centralized exchanges; instead, it used non-custodial wallets. Technically, non-custodial wallets (cold or hardware wallets) are considered the ultimate safeguard for crypto assets; unlike exchange accounts, which can be frozen by legal orders, these wallets function as personal vaults accessible only by the holder of the private key.

Bitcoin uses on-chain addresses to identify asset ownership and flow. Possession of an address’s private key grants full control over the bitcoins at that address. Blockchain analytics show the bitcoins held by the U.S. government closely correspond to those stolen in the LuBian hack. Records indicate that at 2020-12-29 UTC, LuBian’s core Bitcoin wallet addresses underwent abnormal transfers totaling 127,272.06953176 BTC. This is consistent with the DOJ’s figure. The attackers left the stolen bitcoins dormant until June 2024. Between June 22 and July 23, 2024 UTC, they were transferred to new addresses and remain unmoved. Leading blockchain analytics platform ARKHAM has flagged these final addresses as U.S. government-held. The DOJ has not yet disclosed how Chen Zhi’s bitcoin private keys were obtained.

Figure 1: Key Activity Timeline

2. Attack Chain Analysis

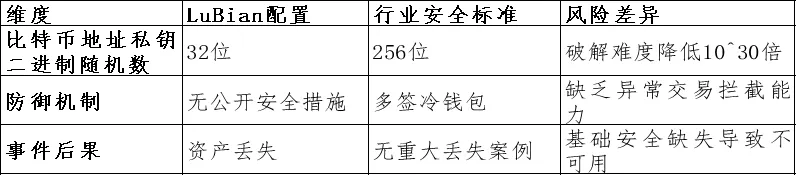

Random number generation is fundamental to cryptographic security in the blockchain ecosystem. Bitcoin uses asymmetric encryption, and its private keys are 256-bit random numbers—brute-forcing would require 2^256 attempts, which is practically impossible. However, if a private key is not truly random (for example, only 32 bits are random while 224 bits are predictable), its strength drops drastically, making brute-forcing feasible at 2^32 (about 4.29 billion) attempts. A notable example: in September 2022, UK crypto market maker Wintermute lost $160 million due to a similar pseudo-random number generator (PRNG) flaw.

In August 2023, the MilkSad security team publicly disclosed a pseudo-random number generator (PRNG) vulnerability in a third-party key generation tool and registered CVE-2023-39910. Their research highlighted a similar flaw in the LuBian mining pool, and all 25 bitcoin addresses listed in the DOJ indictment were affected.

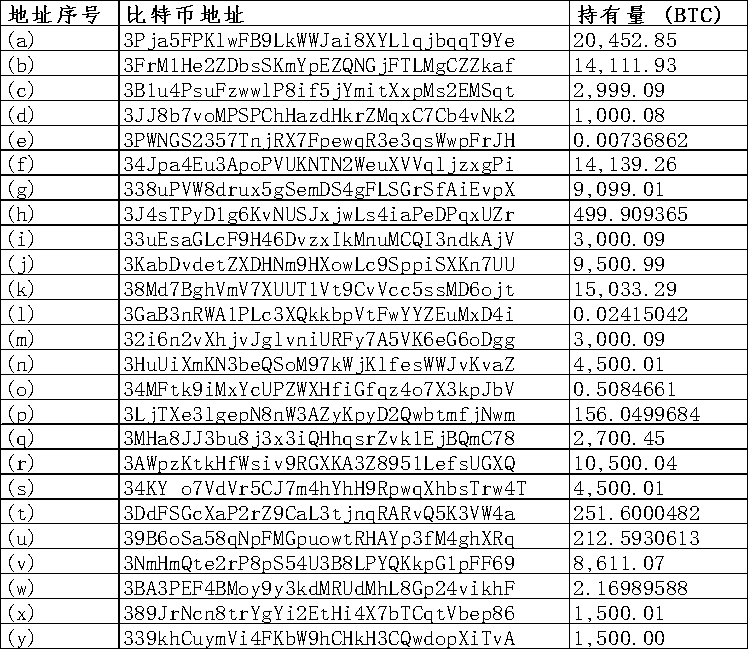

Figure 2: 25 Bitcoin Wallet Addresses Listed in DOJ Indictment

LuBian’s non-custodial wallet system relied on a custom private key generation algorithm that used only 32-bit randomness instead of the recommended 256-bit standard—a critical vulnerability. The algorithm depended on weak inputs such as timestamps for seeding the Mersenne Twister (MT19937-32) PRNG, which offers only 4 bytes of randomness and can be efficiently brute-forced. Mathematically, the probability of cracking is 1/2^32. For example, an attack script testing 1,000,000 keys per second would take roughly 4,200 seconds (1.17 hours). Tools like Hashcat or custom scripts could speed this up even further. Attackers exploited this weakness to steal a vast amount of Bitcoin from LuBian.

Figure 3: LuBian Mining Pool vs. Industry Security Standards Comparison

Technical tracing reveals the hack’s complete timeline and details:

1. Attack and Theft Stage: 2020-12-29 UTC

Event: Hackers exploited the pseudo-random number generator (PRNG) flaw in LuBian’s wallet private key generation, brute-forcing over 5,000 weak wallet addresses (type: P2WPKH-nested-in-P2SH, prefix 3). Within about two hours, 127,272.06953176 BTC (then valued at $3.5 billion) were drained, leaving under 200 BTC. All suspicious transactions shared the same fee, indicating automated bulk transfer scripts.

Sender: Group of weak wallet addresses controlled by LuBian’s mining operation (affiliated with Prince Group);

Receiver: Attacker-controlled bitcoin wallet addresses (undisclosed);

Transfer Path: Weak wallet addresses → Attacker wallet addresses;

Correlation: Stolen total of 127,272.06953176 BTC matches the DOJ’s 127,271 BTC figure.

2. Dormancy Stage: 2020-12-30 to 2024-06-22 UTC

Event: The stolen bitcoins stayed in attacker-controlled wallet addresses for four years, virtually untouched, except for minor “dust” transactions likely intended for testing.

Correlation: The coins remained unmoved until the U.S. government’s full takeover in June 2024, inconsistent with typical hackers’ rapid monetization, suggesting nation-state involvement.

3. Recovery Attempt Stage: Early 2021, July 4 and 26, 2022 UTC

Event: During dormancy, LuBian sent over 1,500 blockchain messages (incurring 1.4 BTC in fees) via Bitcoin’s OP_RETURN opcode, urging the hacker to return the funds and offering a reward. Examples: “Please return our funds, we’ll pay a reward.” On July 4 and 26, 2022, further OP_RETURN messages were sent, such as “MSG from LB. To the white hat who is saving our asset, you can contact us through 1228btc@ gmail.com to discuss the return of asset and your reward.”

Sender: Weak wallet addresses controlled by LuBian’s mining operation (affiliated with Prince Group);

Receiver: Attacker-controlled bitcoin wallet addresses;

Transfer Path: Weak wallet addresses → Attacker wallet addresses; transactions embedded with OP_RETURN;

Correlation: These messages confirm repeated attempts by LuBian to reach “third-party hackers” to recover assets and negotiate a ransom.

4. Activation and Transfer Stage: 2024-06-22 to 2024-07-23 UTC

Event: The attackers activated and transferred the bitcoins in their controlled wallets to final wallet addresses. ARKHAM identified these as U.S. government-held.

Sender: Attacker-controlled bitcoin wallet addresses;

Receiver: Consolidated final wallet addresses (undisclosed, but confirmed as U.S. government-controlled);

Transfer Path: Attacker wallet addresses → U.S. government wallet addresses;

Correlation: These assets, dormant for four years, ultimately came under U.S. government control.

5. Announcement and Seizure Stage: October 14, 2025 (U.S. local time)

Event: The U.S. DOJ issued a notice of charges against Chen Zhi and “seized” 127,000 bitcoins from him.

All bitcoin transactions are publicly traceable on the blockchain. This report traced the origins of the stolen bitcoins from LuBian’s weak wallet addresses (controlled by LuBian mining, possibly affiliated with Prince Group). The total stolen was 127,272.06953176 BTC, sourced from roughly 17,800 mined bitcoins, 2,300 pool payout coins, and 107,100 coins from exchanges and other sources. Preliminary results indicate discrepancies with the DOJ’s claim that all funds were illicit.

3. Vulnerability Technical Analysis

1. Bitcoin Wallet Address Private Key Generation:

LuBian’s vulnerability stemmed from a private key generator flaw similar to the “MilkSad” bug in Libbitcoin Explorer. LuBian’s system used the Mersenne Twister (MT19937-32) PRNG, seeded with just 32 bits, providing only 32 bits of entropy. This PRNG is not cryptographically secure, making it predictable and easily reverse-engineered. Attackers could enumerate all possible 32-bit seeds (0 to 2^32-1), generate corresponding private keys, and check for matches with known wallet hashes.

Typically, Bitcoin private keys are generated as: random seed → SHA-256 hash → ECDSA private key.

LuBian’s implementation may have used custom or open-source code (like Libbitcoin), but neglected entropy security. Like the MilkSad flaw, Libbitcoin Explorer’s “bx seed” command uses MT19937-32 seeded with timestamps or weak inputs, making brute-force attacks feasible. The LuBian hack affected over 5,000 wallets, indicating a systemic flaw—possibly from batch wallet generation.

2. Simulated Attack Workflow:

(1) Identify target wallet addresses (via on-chain monitoring of LuBian activity);

(2) Enumerate 32-bit seeds: for seed in 0 to 4294967295;

(3) Generate private key: private_key = SHA256(seed);

(4) Derive public key and address: use ECDSA SECP256k1 curve;

(5) Match: if the derived address matches the target, use the private key to sign and steal funds;

Comparison: The vulnerability resembles Trust Wallet’s 32-bit entropy flaw, which led to widespread bitcoin wallet compromise. The MilkSad bug in Libbitcoin Explorer also stemmed from low entropy. These issues are legacy code problems from not adopting the BIP-39 standard (12–24 word seed phrases, offering high entropy). LuBian likely used a custom algorithm for management convenience, but compromised security.

Defensive gaps: LuBian did not use multisignature wallets, hardware wallets, or hierarchical deterministic (HD) wallets—measures that boost security. On-chain data shows the attack spanned multiple wallets, indicating a systemic vulnerability rather than a single point of failure.

3. On-Chain Evidence and Recovery Attempts:

OP_RETURN messages: LuBian sent over 1,500 OP_RETURN messages, incurring 1.4 BTC in fees, to request the return of funds. These messages are embedded in the blockchain, proving genuine ownership. Example messages include “please return funds,” distributed across multiple transactions.

4. Attack Correlation Analysis:

The DOJ’s October 14, 2025 indictment against Chen Zhi (case 1:25-cr-00416) lists 25 bitcoin wallet addresses holding approximately 127,271 BTC (valued at $15 billion), all seized. Blockchain analysis and official documents show high correlation with the LuBian hack:

Direct correlation: Blockchain analysis confirms the 25 addresses in the DOJ indictment are the final holding addresses for the bitcoins stolen in the LuBian 2020 hack. Elliptic’s report notes these bitcoins were stolen from LuBian’s mining operation. Arkham Intelligence confirms the seized funds stem from the LuBian theft.

Indictment evidence: Though the DOJ indictment doesn’t name “LuBian hack” directly, it cites funds stolen from “Iranian and Chinese bitcoin mining operations,” matching Elliptic’s and Arkham’s blockchain findings.

Behavioral correlation: The stolen bitcoins remained dormant for four years after the 2020 hack, with only minor dust transactions, until the U.S. government’s takeover in 2024. This atypical inactivity for hackers suggests nation-state involvement. Analysis suggests the U.S. government may have gained control as early as December 2020.

4. Impact and Recommendations

The 2020 LuBian hack had deep repercussions, resulting in the mining pool’s dissolution and the loss of over 90% of its assets. The stolen bitcoins are now worth $15 billion, underscoring how price volatility amplifies risk.

This incident exposes systemic risks in random number generation across the crypto toolchain. To prevent similar vulnerabilities, the blockchain sector should use cryptographically secure PRNGs. It should also implement layered defenses, such as multisignature wallets, cold storage, and periodic audits, and avoid custom private key algorithms. Mining pools should deploy real-time on-chain monitoring and anomaly alerts. Individual users should avoid unverified open-source key generation modules. The event also demonstrates that, despite blockchain’s transparency, weak security foundations can lead to devastating consequences—highlighting the importance of cybersecurity for digital assets and the future digital economy.

Statement:

- This article is reprinted from [National Computer Virus Emergency Response Center] and copyright belongs to the original author [National Computer Virus Emergency Response Center]. For reprint objections, please contact the Gate Learn team, who will promptly address them according to relevant procedures.

- Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions of this article are translated by the Gate Learn team and may not be copied, distributed, or plagiarized unless Gate is credited.

Related Articles

False Chrome Extension Stealing Analysis

Analysis of the Sonne Finance Attack

What is a Crypto Card and How Does it Work? (2025)

Introduction to the Aleo Privacy Blockchain

Understanding the Babylon Protocol: The Hanging Gardens of Bitcoin