Base is leaving, Optimism will not stay.

Key Takeaways

- Revenue is highly concentrated: In 2025, Base generated roughly 71% of all Superchain sequencer revenue, and this concentration is increasing. Yet, Coinbase’s payment to Optimism is capped at just 2.5%.

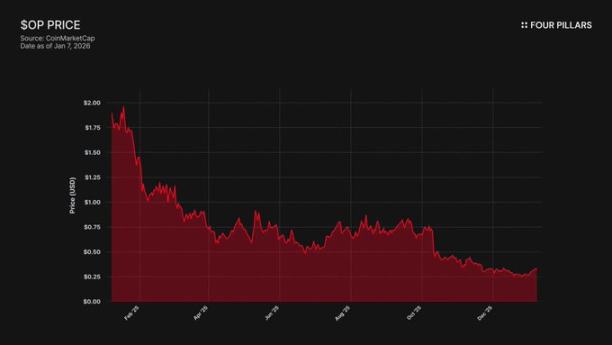

- Price diverges from ecosystem growth: OP tokens have plummeted 93% from their peak ($4.84 → $0.32), while Base’s total value locked (TVL) surged 48% in the same period ($3.1 billion → $5 billion). The market recognizes that Base’s growth doesn’t benefit OP holders, but hasn’t fully priced in the risk of Base’s potential exit.

- No technical barrier: OP Stack is governed by the MIT open-source license, allowing Coinbase to fork it at any time. The only remaining link between Base and Superchain is governance. If BASE launches an independent governance token, that connection is severed.

- Alliance is fragile: Optimism awarded Base 118 million OP tokens to secure long-term cooperation, but capped its voting rights at 9% of total supply. This isn’t true alignment—it’s a minority stake with an “exit option.” If renegotiation drives OP’s price down, forfeiting the grant for the benefit of canceling revenue sharing is a rational trade for Coinbase.

Base, Coinbase’s L2 network, contributed about 71% of Superchain’s sequencer revenue in 2025, but paid only 2.5% to the Optimism Collective. OP Stack’s MIT license means nothing—technically or legally—prevents Coinbase from using exit threats to renegotiate terms, or from building independent infrastructure that renders Superchain membership meaningless. OP holders face single-counterparty revenue dependence and significant downside risk, and we believe the market hasn’t fully recognized this exposure.

1. Extracting 71% of Revenue, Paying Only 2.5% “Rent”

When Optimism and Base signed their agreement, they assumed no single chain would dominate Superchain’s ecosystem, keeping revenue sharing balanced. Fees are split by the higher of “2.5% of chain revenue” or “15% of on-chain profit (revenue minus L1 gas costs),” which seemed reasonable for a collaborative, diverse rollup ecosystem.

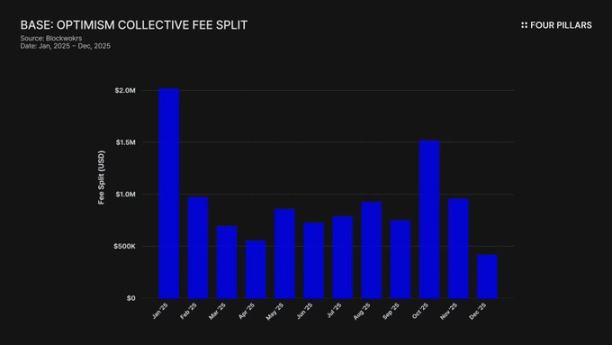

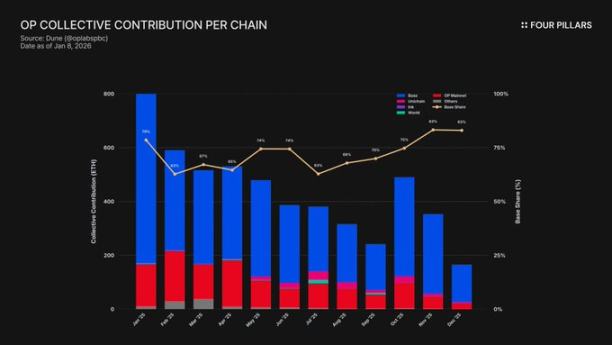

That assumption proved wrong. In 2025, Base generated $74 million in chain revenue—over 71% of all OP chain sequencer fees—yet only paid 2.5% to the Optimism Collective. Coinbase captured 28 times more value than it paid. By October 2025, Base’s TVL reached $5 billion (up 48% in six months), marking the first Ethereum L2 to cross this milestone. Its dominance only continues to grow.

This imbalance is exacerbated by the subsidy mechanism. While Base leads revenue generation, the OP mainnet—sharing 100% of its profits with the Collective—bears a disproportionate burden for ecosystem contributions. In effect, OP mainnet is subsidizing the alliance’s political cohesion, while its largest member pays the smallest share.

Where do these fees go? According to Optimism’s documentation, sequencer revenue flows into the Optimism Collective treasury. To date, this treasury has accumulated over $34 million from Superchain fees, but none of these funds have been spent or allocated to specific projects.

The “flywheel” concept (fees fund public goods → public goods expand the ecosystem → ecosystem generates more fees) hasn’t materialized. Current initiatives—RetroPGF and ecosystem grants—are funded by new OP token issuance, not ETH from the treasury. This undermines the core value proposition of joining Superchain. Base contributes about $1.85 million per year to the treasury, but the treasury provides no direct economic return to member chains paying in.

Governance participation highlights the same issue. In January 2024, Base published its “Declaration of Participation in Optimism Governance.” Since then, there’s been no public activity—no proposals, no forum discussion, no visible governance engagement. Despite contributing over 70% of Superchain’s economic value, Base is largely absent from the governance process it claims to support. Even Optimism’s own governance forum rarely mentions Base. “Shared governance” is little more than theory for both sides.

Thus, Superchain membership’s “value” is entirely future-facing—future interoperability, future governance influence, future network effects. For a publicly traded company accountable to shareholders, “future value” is a tough sell when current costs are real and ongoing.

The core question: Does Coinbase have any economic incentive to maintain the current arrangement? And what happens if they decide otherwise?

2. Forking Is Always on the Table

This is the legal reality behind every Superchain relationship: OP Stack is a public good under the MIT license. Anyone can freely clone, fork, or deploy it without permission.

So why do chains like Base, Mode, Worldcoin, and Zora remain in Superchain? Optimism’s documentation points to “soft constraints”: shared governance, shared upgrades and security, ecosystem funds, and the legitimacy of the Superchain brand. Chains join voluntarily, not by force.

This distinction is critical when assessing OP’s risk.

What would Coinbase lose by forking? Participation in Optimism governance, the “Superchain” brand, and coordinated protocol upgrades.

What would they keep? 100% of their $5 billion TVL, all users, all Base applications, and more than $74 million in annual sequencer revenue.

“Soft constraints” only matter if Base needs something from Optimism that it can’t build or buy. The evidence shows Base is already building this independence. In December 2025, Base launched a Solana bridge using Coinbase’s infrastructure and Chainlink CCIP, not Superchain’s interoperability. Base isn’t waiting for Superchain’s solution.

We’re not saying Coinbase will fork tomorrow. The point is, the MIT license itself is a ready-made “exit option,” and Coinbase’s recent moves show they’re actively reducing reliance on Superchain. A BASE token with independent governance would complete this shift, turning “soft constraints” into mere ceremony.

For OP holders, the question is simple: If Base’s only reason to stay is the appearance of an “ecosystem alliance,” what happens when Coinbase decides the alliance is no longer worth it?

3. Negotiations Are Already Underway

“Starting to explore”—the standard phrase for any L2 in the 6–12 months before launching a token.

In September 2025, Jesse Pollak announced at BaseCamp that Base was “starting to explore” launching a native token. He emphasized “no clear plan yet” and that Coinbase “does not intend to announce a launch date soon.” This is notable because until late 2024, Coinbase had explicitly said it had no plans for a Base token. The announcement followed Kraken’s Ink Network unveiling its INK token, signaling a shift in the L2 token landscape.

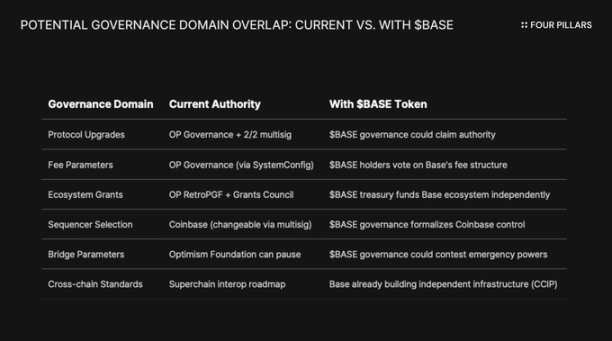

The language is as telling as the substance. Pollak described the token as “a powerful lever for expanding governance, aligning developer incentives, and opening new design pathways.” These are not neutral terms. Protocol upgrades, fee parameters, ecosystem grants, sequencer selection—currently governed by Superchain. A BASE token with governance rights over these decisions would overlap Optimism’s governance, giving Coinbase greater economic control.

To understand why a BASE token would fundamentally change the relationship, you have to understand Superchain’s current governance structure.

Optimism Collective uses a bicameral system:

- Token House (OP holders): Votes on protocol upgrades, grants, and governance proposals.

- Citizen House (badge holders): Votes on RetroPGF fund allocations.

Base upgrades are controlled by a 2/2 multisig wallet, with signers from both Base and the Optimism Foundation—neither side can unilaterally upgrade Base contracts. Once fully implemented, the Security Council will “execute upgrades as directed by Optimism governance.”

This structure gives Optimism shared, not unilateral, control over Base. The 2/2 multisig is a check and balance: Optimism can’t force upgrades Base opposes, and Base can’t upgrade without Optimism’s approval.

If Coinbase follows the ARB/OP governance token model, structural conflict is inevitable. If BASE holders vote on protocol upgrades, whose decision prevails—BASE or OP governance? If BASE has its own grants, why would Base developers wait for RetroPGF? If BASE governance controls sequencer selection, what’s left for the 2/2 multisig?

Crucially, Optimism governance can’t prevent Base from issuing a token with overlapping governance. The “Law of Chains” sets user protection and interoperability standards, but doesn’t restrict what chain governors do with their own tokens. Coinbase could launch a BASE token with full protocol governance tomorrow, and Optimism’s only recourse would be political pressure—the already-weak “soft constraint.”

There’s another angle—the constraints of being a public company. This would be the first token generation event led by a publicly traded firm. Traditional launches and airdrops aim to maximize value for private investors and founders, but Coinbase owes a fiduciary duty to COIN shareholders. Any token distribution must prove it enhances Coinbase’s enterprise value.

This changes the calculus. Coinbase can’t simply airdrop tokens for community goodwill. They need a structure that boosts COIN’s stock price. One method: use BASE tokens as leverage to renegotiate and lower Superchain’s revenue share, increasing Base’s retained earnings and ultimately improving Coinbase’s financials.

4. The “Reputational Risk” Argument Doesn’t Hold Up

The strongest rebuttal to this thesis is that Coinbase, as a public company, positions itself as a model of “compliance and cooperation” in crypto. Forking OP Stack to save a few million dollars in annual revenue would seem petty and risk its brand. This deserves careful consideration.

Superchain does deliver real value. Its roadmap includes native cross-chain messaging, and total value locked across all Ethereum L2s peaked at about $55.5 billion in December 2025. Base benefits from composability with OP mainnet, Unichain, and Worldchain. Abandoning these network effects comes at a cost.

There’s also the 118 million OP token grant. To cement a “long-term alliance,” the Optimism Foundation gave Base the opportunity to receive about 118 million OP tokens over six years. At the time, the grant was worth about $175 million.

But this defense misses the real risk. The argument assumes a public, aggressive fork. More likely is a quiet renegotiation: Coinbase uses BASE tokens as leverage to secure better terms inside Superchain. Such talks may not even make headlines outside governance forums.

Consider interoperability. Base has already built its own Solana bridge using CCIP, independent of Optimism’s solution. They’re not waiting for Superchain’s interoperability—they’re building their own cross-chain infrastructure. When you solve problems yourself, “shared upgrades and security” as soft constraints lose relevance.

Consider the OP grant. Base’s voting or delegation power from this grant is capped at 9% of the votable supply. This isn’t deep alignment—it’s a minority stake with limited governance rights. Coinbase can’t use 9% to control Optimism, and Optimism can’t use it to control Base. At today’s price ($0.32), the entire 118 million grant is worth about $38 million. If renegotiation triggers a 30% OP price drop due to lower Base revenue, Coinbase’s paper loss is trivial compared to permanently canceling or sharply reducing revenue sharing.

Reducing the annual revenue share on $74 million from 2.5% to 0.5% would save Coinbase over $1.4 million per year, permanently. By comparison, a one-time $10 million markdown on the OP grant is a rounding error.

Institutional investors aren’t interested in Superchain politics. They care about Base’s TVL, trading volume, and Coinbase’s profits. A renegotiated revenue share won’t move COIN’s stock. It’ll just show up as a routine governance update on Optimism’s forum and slightly improve Coinbase’s L2 margins.

5. A Single Revenue Stream with an “Exit Option”

We believe OP isn’t yet priced as an asset with counterparty risk—but it should be.

OP has dropped 93% from its all-time high of $4.84 to about $0.32, with a circulating market cap near $620 million. The market has already repriced OP downward, but we believe it hasn’t fully absorbed the structural risks baked into Superchain’s economic model.

The divergence is clear. Base’s TVL climbed from $3.1 billion in January 2025 to a peak of $5.6 billion in October. Base is winning, OP holders are not. User attention has shifted almost entirely to Base, and despite new partners, OP mainnet still trails in everyday usage.

Superchain looks like a decentralized collective, but economically it’s heavily dependent on a single counterparty—one with every incentive to renegotiate.

Consider revenue concentration: Base delivers over 71% of all sequencer income to the Optimism Collective. OP mainnet’s high contribution isn’t due to rapid growth, but because it shares 100% of profits, while Base shares only 2.5% or 15%.

Now, consider OP holders’ asymmetric reward structure:

- If Base stays and grows: OP captures just 2.5% of the revenue. Base keeps 97.5%.

- If Base renegotiates to ~0.5%: OP loses about 80% of revenue from Base. The largest economic contributor becomes negligible.

- If Base exits: OP loses its economic engine overnight.

In every scenario, upside is capped while downside risk is open-ended. You’re long on a revenue stream, but the largest payer holds all the leverage—including an MIT license exit option and a new token that could establish independent governance at any time.

The market seems to have priced in the fact that “Base’s growth doesn’t benefit OP holders,” but hasn’t priced in exit risk—the chance that Coinbase leverages BASE tokens to renegotiate terms, or worse, gradually exits Superchain governance altogether.

Disclaimer:

- This article is republished from [Foresight News]. Copyright belongs to the original author [@ 13300RPM, Four Pillars]. If you have any objections to republication, please contact the Gate Learn team, which will process in accordance with relevant procedures.

- Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions are translated by the Gate Learn team. Do not copy, distribute, or plagiarize translated articles without referencing Gate.

Related Articles

The Future of Cross-Chain Bridges: Full-Chain Interoperability Becomes Inevitable, Liquidity Bridges Will Decline

Solana Need L2s And Appchains?

Sui: How are users leveraging its speed, security, & scalability?

Navigating the Zero Knowledge Landscape

What is Tronscan and How Can You Use it in 2025?