From Libya to Iran: Power Cuts for Nations, Nonstop Bitcoin Miners

Introduction: The “Export Industry” of Blackout Nations—How Electricity Becomes Bitcoin

Tehran’s summer nights are stifling, the heat pressing in like an unyielding net that makes it hard to breathe.

The summer of 2025 marked the most punishing power crisis in recent years for Iran’s capital. That year, the city endured one of the most extreme heatwaves in nearly fifty years, with temperatures repeatedly exceeding 40°C. Twenty-seven provinces faced forced electricity rationing, and numerous government offices and schools closed. In local hospitals, doctors had to rely on diesel generators for power—if the blackout lasted too long, ventilators in intensive care units could shut down.

Yet on the city’s outskirts, behind high walls, a different sound dominates: industrial fans roar as rows of Bitcoin miners run at full capacity. LED indicators flash like stars in the night, and here, the power almost never goes out.

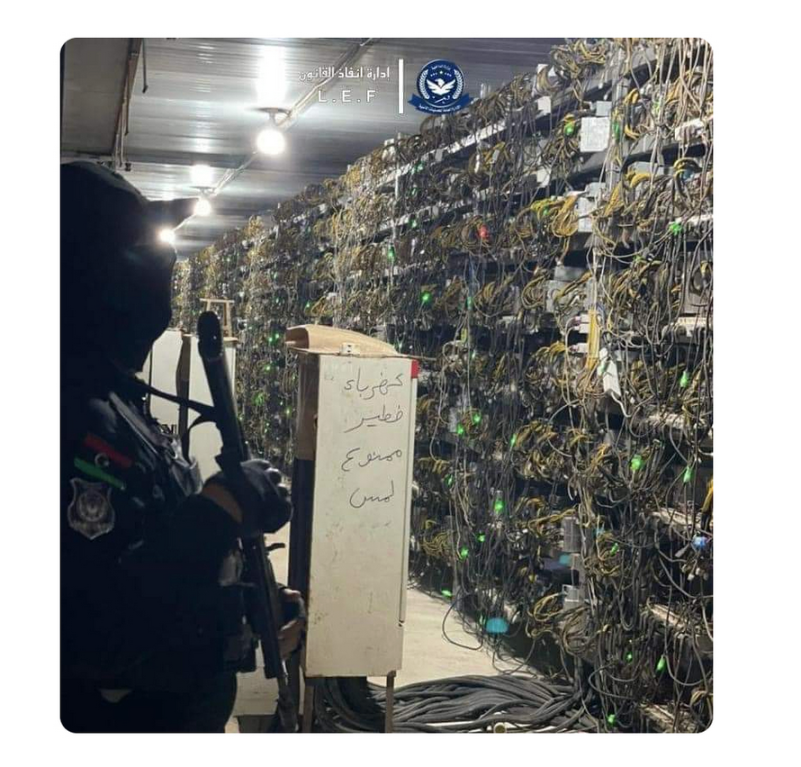

Across the Mediterranean, Libya sees the same pattern daily. In the eastern region, residents endure rolling blackouts of six to eight hours each day. Food spoils in refrigerators, and children do homework by candlelight. But in an abandoned steel plant outside the city, smuggled old mining rigs run nonstop, converting the country’s nearly free electricity into Bitcoin, which is then exchanged for dollars through crypto exchanges.

This is one of the 21st century’s most surreal energy stories: in two nations battered by sanctions and civil war, electricity is no longer just a public utility—it has become a “hard currency” for export.

Image description: Two Iranian men sit outside their cell phone shop, lit only by an emergency lamp as a blackout leaves the street in darkness.

Chapter One: Power Runs—When Energy Becomes a Financial Instrument

Bitcoin mining is, at its core, an energy arbitrage game. Anywhere electricity is cheap enough, mining rigs can turn a profit. In Texas or Iceland, mine operators meticulously calculate costs per kilowatt-hour, and only the latest, most efficient rigs survive. In Iran and Libya, however, the rules are entirely different.

Iran’s industrial electricity rates drop as low as $0.01 per kWh; Libya’s residential rates are even lower, around $0.004 per kWh—among the lowest globally. These prices are possible only because governments provide massive fuel subsidies and artificially suppress electricity costs. In a normal market, such rates wouldn’t even cover generation costs.

For miners, it’s a goldmine. Even outdated rigs discarded in China or Kazakhstan—devices considered electronic waste in developed countries—can easily turn a profit here. Official data shows that in 2021, Libya’s Bitcoin hashrate accounted for about 0.6% of global output, surpassing all other Arab and African nations and even some European economies.

That figure may seem small, but in Libya’s context, it’s astonishing. The country has just 7 million people, a grid loss rate of 40%, and daily rolling blackouts. At peak, Bitcoin mining consumed about 2% of Libya’s total electricity output—roughly 0.855 terawatt-hours (TWh) per year.

Iran’s situation is even more extreme. With the world’s fourth-largest oil reserves and second-largest natural gas reserves, Iran shouldn’t face power shortages. Yet US sanctions have cut off access to advanced generation equipment and technology, and aging infrastructure and chaotic management keep the power supply under constant strain. The explosive growth of Bitcoin mining is pushing the grid to its breaking point.

This isn’t typical industrial expansion. It’s a run on public resources—when electricity becomes a “hard currency” that bypasses the financial system, it no longer serves hospitals, schools, or residents first, but instead flows to machines that can turn it into dollars.

Chapter Two: Two Nations, Twin Mining Histories

Iran: From “Exporting Energy” to “Exporting Hashrate”

Under extreme sanctions, Iran legalized Bitcoin mining, transforming cheap domestic electricity into globally liquid digital assets.

In 2018, the Trump administration withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal and reimposed “maximum pressure” sanctions. Iran was ejected from the SWIFT system, lost access to dollars in global trade, saw oil exports plunge, and foreign reserves dry up. In this context, Bitcoin mining offered an alternative for monetizing energy: no SWIFT, no correspondent banks—just electricity, mining rigs, and a channel to sell coins.

In 2019, the Iranian government formally recognized cryptocurrency mining as a legal industry and created a licensing system. The policy looked “modern”: miners could apply for permits, operate with discounted electricity, but had to sell all mined Bitcoin to the Central Bank of Iran.

Theoretically, this was a win-win-win: the state trades cheap electricity for Bitcoin, exchanges Bitcoin for foreign currency or imports; miners earn stable profits; and grid loads can be planned and regulated.

In practice, things quickly went off track: licenses existed, but the gray area was much larger.

By 2021, then-President Rouhani publicly admitted that about 85% of Iran’s mining activity was unlicensed. Underground mines sprang up everywhere—from abandoned factories to mosque basements, government buildings to private homes. The deeper the subsidies, the stronger the incentive for arbitrage; the looser the oversight, the more stealing electricity became an “unspoken benefit.”

With power shortages worsening and illegal mining consuming over 2 gigawatts, the Iranian government announced a nationwide temporary ban on all cryptocurrency mining from May to September—a four-month moratorium, the strictest since legalization in 2019.

During this period, authorities launched large-scale raids: the Ministry of Energy, police, and local officials raided thousands of illegal mines, seizing tens of thousands of rigs in the second half of 2021 alone.

After the ban ended, mining activity quickly rebounded. Many confiscated rigs returned to service, and underground mines grew even larger. The crackdown was widely seen as a brief performance: a show of fighting illegality that failed to address deeper issues, and even allowed some well-connected mines to expand.

More importantly, investigations and reports revealed that entities closely tied to authorities were heavily involved in the sector, operating “privileged mines” with independent power supply and immunity from enforcement.

When these mines are backed by “untouchable hands,” the so-called crackdown becomes political theater. The public narrative is sharper: “We endure darkness just so Bitcoin miners can keep running.”

Source: Financial Times

Libya: Cheap Power, Shadow Mining

Slogans on Libyan street walls denounce “trading in relief supplies as illegal,” highlighting public outrage over unfair resource distribution—a sentiment quietly brewing as mining diverts subsidized electricity.

Libya’s mining story is one of “wild growth amid institutional absence.”

Libya, a North African country (population about 7.3–7.5 million, nearly 1.76 million square kilometers—Africa’s fourth largest), sits on the Mediterranean coast, bordering Egypt, Tunisia, and Algeria. Since the fall of the Gaddafi regime in 2011, the country has endured prolonged turmoil: repeated civil wars, numerous armed factions, and fragmented state institutions—a “fragmented governance” where violence is relatively contained but unified administration is lacking.

What truly turned Libya into a mining hotspot is its bizarre electricity pricing. As one of Africa’s largest oil producers, the government has long subsidized electricity, keeping rates at $0.0040 per kWh—lower than even the fuel cost of generation. In a normal country, such subsidies aim to support livelihoods. In Libya, they’re a massive arbitrage opportunity.

This led to a classic arbitrage model:

- Old rigs discarded in Europe and the US still turn a profit in Libya;

- Industrial zones, abandoned factories, and warehouses are ideal for hiding high-load operations;

- Equipment imports are restricted, but gray channels and smuggling keep machines flowing in;

Although the Central Bank of Libya (CBL) declared virtual currency trading illegal in 2018 and the Ministry of Economy banned mining equipment imports in 2022, mining itself isn’t explicitly outlawed nationwide. Enforcement relies on charges like “illegal electricity use” or “smuggling,” but fragmented authority means these laws are poorly enforced, and gray areas keep expanding.

This “banned but persistent” state is typical of fragmented power—CBL and Ministry bans are hard to enforce in eastern Benghazi or southern regions, and local militias or armed groups sometimes tolerate or protect mining operations, allowing shadow mining to flourish.

Source: @ emad_badi on X

Even more strangely, many of these mines are operated by foreigners. In November 2025, Libyan prosecutors sentenced nine individuals running a mine in the Zliten steel plant to three years in prison, confiscated equipment, and recovered illegal gains. In previous raids, authorities arrested dozens of Asian nationals operating industrial-scale mines with old rigs discarded from China or Kazakhstan.

These outdated machines are unprofitable in developed countries, but in Libya, they’re cash cows. With electricity so cheap, even the least efficient rigs can make money. That’s why Libya has become the resurrection ground for the world’s “mining graveyard”—devices scrapped in Texas or Iceland get a second life here.

Chapter Three: Collapsing Grids and Privatized Energy

Iran and Libya have taken different paths: one tried to integrate Bitcoin mining into state machinery, the other let it operate in the shadows. Both arrived at the same destination—widening grid deficits and political fallout from resource allocation.

This is not just a technical failure; it’s a political economy outcome. Subsidized rates create the illusion that “electricity is worthless,” mining offers the temptation that “electricity can be monetized,” and power structures determine who gets to cash in.

When miners share the grid with hospitals, factories, and residents, the conflict is no longer abstract. Blackouts damage more than refrigerators and air conditioners—they disrupt surgical lamps, blood bank refrigeration, and industrial production lines. Every period of darkness is a silent audit of how public resources are distributed.

The problem is that mining profits are highly “portable.” Electricity is local, with costs borne by society; Bitcoin is global, with value that can be quickly transferred. The result is a highly asymmetric structure: society bears the cost of consumption and outages, while a few reap cross-border profits.

In countries with robust institutions and abundant energy, Bitcoin mining is treated as an industrial activity. In places like Iran and Libya, the issue itself is fundamentally different.

Emerging Industry or Resource Plunder?

Globally, Bitcoin mining is seen as an emerging industry, even a symbol of the “digital economy.” In Iran and Libya, however, it’s more like an experiment in privatizing public resources.

If it truly were an industry, it would create jobs, pay taxes, be regulated, and deliver net social benefits. In both countries, mining is highly automated and creates almost no jobs; most mines operate illegally or semi-legally, tax contributions are limited, and even licensed mines lack transparency about where profits go.

Cheap electricity was originally meant to support the public. In Iran, energy subsidies have been part of the “social contract” since the Islamic Revolution—the government uses oil revenue to subsidize power, and the public accepts authoritarian rule. In Libya, electricity subsidies were central to the welfare system left by Gaddafi.

But when those subsidies are used for Bitcoin mining, their nature fundamentally changes. Electricity ceases to be a public service and becomes a means for a few to generate private wealth. Ordinary people not only fail to benefit—they pay the price: more frequent blackouts, higher diesel generator costs, and weaker healthcare and education.

More importantly, mining hasn’t brought real foreign exchange income to these countries. In theory, Iran requires miners to sell Bitcoin to the central bank, but practical enforcement is questionable. In Libya, no such mechanism exists. Most Bitcoin is exchanged for dollars or other currencies on overseas platforms, then transferred abroad through underground banks or crypto channels. These funds don’t enter state coffers or return to the real economy—they become private wealth for a few.

In this sense, Bitcoin mining resembles a new kind of “resource curse.” It doesn’t create wealth through production or innovation, but exploits price distortions and institutional loopholes to capture public resources. The cost is borne by the most vulnerable.

Conclusion: The True Cost of a Bitcoin

In a world of tightening resources, electricity is no longer just a tool to light the darkness—it is a commodity to be converted, traded, and even plundered. When nations treat electricity as an “exportable hard currency,” they are consuming what should be reserved for public welfare and future development.

The issue isn’t Bitcoin itself, but who controls the allocation of public resources. When this power is unchecked, the so-called “industry” becomes just another form of plunder.

And those sitting in the dark are still waiting for the lights to come back on.

Disclaimer:

- This article is republished from [ForesightNews]. Copyright belongs to the original author [On-Chain Revelation]. If you have any objections to this republication, please contact the Gate Learn team. The team will process your request according to relevant procedures as soon as possible.

- Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions of this article are translated by the Gate Learn team. Unless Gate is mentioned, translated articles may not be copied, distributed, or plagiarized.

Related Articles

The Future of Cross-Chain Bridges: Full-Chain Interoperability Becomes Inevitable, Liquidity Bridges Will Decline

Solana Need L2s And Appchains?

Sui: How are users leveraging its speed, security, & scalability?

Navigating the Zero Knowledge Landscape

What is Tronscan and How Can You Use it in 2025?